“But what gave this pestilence particularly severe force was that whenever the diseased mixed with healthy people, like a fire through dry grass or oil, it would run upon the healthy.”

—Boccaccio’s description of the plague in Florence in his classic Decameron, published in 1350 191

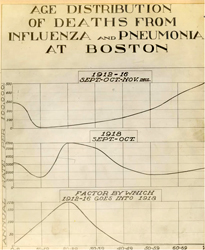

Click here for a printer-friendly version of this pageH5N1 shares another ominous trait with the virus of 1918: They both have a taste for the young. One of the greatest mysteries of the 1918 pandemic was, in the words of then Acting Surgeon General of the Army, why “the infection, like war, kills the young vigorous robust adults.”192 As the American Public Health Association put it rather crudely at the time: “The major portion of this mortality occurred between the ages of 20 and 40, when human life is of the highest economic importance.”193

Seasonal influenza, on the other hand, tends to seriously harm only the very young or the very old. The death of the respiratory lining that triggers fits of coughing accounts for the sore throat and hoarseness that typically accompany the illness. The mucus-sweeping cells are also killed, which opens up the body for a superimposed bacterial infection on top of the viral infection. This bacterial pneumonia is typically how stricken infants and elderly may die during flu season every year. Their immature or declining immune systems are unable to fend off the infections in time.

The resurrection of the 1918 virus offered a chance to solve the great mystery. The reason the healthiest people were the most at risk, researchers discovered, was that the virus tricked the body into attacking itself—it used our own immune systems against us.

Those who suffer anaphylactic reactions to bee stings or food allergies know the power of the human immune system. In their case, exposure to certain foreign stimuli can trigger a massive overreaction of the body’s immune system that, without treatment, could literally drop them dead within minutes. Our immune systems are equipped to explode at any moment, but there are layers of fail-safe mechanisms that protect most people from such an overreaction. The influenza virus has learned, though, how to flick off the safety.

Both the 1918 virus and the current threat, H5N1, seem to trigger a “cytokine storm,” an overexuberant immune reaction to the virus. In laboratory cultures of human lung tissue, infection with the H5N1 virus led to the production of ten times the level of cytokines induced by regular seasonal flu viruses.194 The chemical messengers trigger a massive inflammatory reaction in the lungs. “It’s kind of like inviting in trucks full of dynamite,” says the lead researcher who first discovered the phenomenon with H5N1.1195

While cytokines are vital to antiviral defense, the virus may trigger too much of a good thing.196 The flood of cytokines overstimulates immune components like Natural Killer Cells, which go on a killing spree, causing so much collateral damage that the lungs start filling up with fluid. “It actually turns your immune system on its head, and it causes that part to be the thing that kills you,” explains Osterholm.197 “All these cytokines get produced and [that] calls in every immune cell possible to attack yourself. It’s how people die so quickly. In 24 to 36 hours, their lungs just become bloody rags.”198

People between 20 and 40 years of age tend to have the strongest immune systems. You spend the first 20 years of your life building up your immune system, and then, starting around age 40, the system’s strength begins to wane. That is why this age range is particularly vulnerable, because it’s your own immune system that may kill you.199 A new dog learning old tricks, H5N1 may be following in the 1918 virus’s footsteps.200

Either we wipe out the virus within days or the virus wipes out us. The virus doesn’t care either way. By the time the host wins or dies, it expects to have moved on to virgin territory—and in a dying host, the cytokine storm may even produce a few final spasms of coughing, allowing the virus to jump the burning ship. As one biologist recounted, the body’s desperate shotgun approach to defending against infection is “somewhat like trying to kill a mosquito with a machete—you may kill that mosquito, but most of the blood on the floor will be yours.”201