Stressful

Click here for a printer-friendly version of this pageOvercrowding may also increase the vulnerability for each individual animal. Frederick Murphy, dean emeritus of the School of Veterinary Medicine at the University of California–Davis, has noted how these changes in the way we now raise animals for food “often allow pathogens to enter the food chain at its source and to flourish, largely because of stress-related factors.”1728 The physiological stress created by crowded confinement can have a “profound” impact on immunity,1729 predisposing animals to infection.1730 Diminished immune function means diminished protective responses to vaccinations. “As vaccinal immunity is compromised by factors such as…immunosuppressive stress,” writes a leading1731 USDA expert on chicken vaccines, “mutant clones have an increased opportunity to selectively multiply and to be seeded in the environment.”1732 Studies exposing birds to stressful housing conditions provide “solid evidence in support of the concept that stress impairs adaptive immunity in chicken.”1733

Chickens placed in overcrowded pens develop, over time, “increased adrenal weight”—a swelling growth of the glands that produce stress hormones like adrenaline—while, at the same time, experiencing “regression of lymphatic organs,” a shriveling of the organs of the immune system.1734 This is thought to demonstrate a metabolic trade-off in which energies invested in host defense are diverted by the stress response,1735 which can result in “extensive immunosuppression.”1736 Europe’s Scientific Veterinary Committee reported that one of the reasons Europe is phasing out battery cages for egg-laying hens is that evidence suggests caged chickens may have higher rates of infections “as the stresses from being caged compromise immune function.”1737

Leading meat industry consultant Temple Grandin, an animal scientist at Colorado State University, described the stresses of battery-cage life in an address to the National Institute of Animal Agriculture. “When I visited a large egg layer operation and saw old hens that had reached the end of their productive life, I was horrified. Egg layers bred for maximum egg production…were nervous wrecks that had beaten off half their feathers by constant flapping against the cage.”1738 Referring to egg industry practices in general, Grandin noted, “It’s a case of bad becoming normal.”1739

Under intensive confinement conditions, not only may the birds be unable to comfortably turn around or even stand freely, but the most basic of natural behaviors such as feather preening may be frustrated, leading to additional stress.1740 Overcrowding may disrupt the birds’ natural pecking order, imposing a social stress that has been shown for more than 30 years to weaken resistance to viral infection1741 and, more recently, a multitude of other disease challenges.1742 Industry specialists concede it “proven” that “high stress levels, like the ones modern management practices provoke,” lead to a reduced immune response.1743

Breeding sows are typically confined in metal stalls or crates so narrow they can’t turn around. Prevented from performing normal maternal behavior (and, clearly, physical behavior), the pigs produce lower levels of antibodies in response to an experimental challenge.1744 “Forget the pig is an animal,” an industry journal declared decades ago. “Treat him just like a machine in a factory.”1745 Measures as simple as providing straw bedding for pigs may improve immune function. “Studies suggest,” reads a 2005 review, “that the stress of lying on bare concrete may reduce resistance to respiratory disease leading to increased infection risk.”1746 German researchers found specifically that straw bedding was linked to decreased risk of infection with the influenza virus.1747

Another source of stress for many birds raised for meat and eggs is the wide variety of mutilations they may endure. Bits of body parts of unanesthetized birds—such as their combs, their spurs, and their claws—can be cut off to limit the damage of often stress-induced aggression. Sometimes, toes are snipped off at the first knuckle for identification purposes.1748 University of Georgia poultry scientist Bruce Webster described the broiler chicken at an American Meat Institute conference as “essentially an overgrown baby bird, easily hurt, sometimes treated like bowling balls.”1749

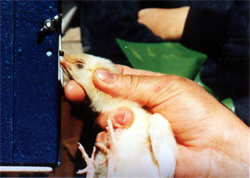

Most egg laying hens in the United States are “beak-trimmed.”1750 Parts of baby chicks’ beaks are sliced off with a hot blade, an acutely painful1751 procedure shown to impair their ability to grasp and swallow feed.1752 Already banned in some European countries as unnecessary,1753 the procedure is viewed by some poultry scientists as no more than a “stop-gap measure masking basic inadequacies in environment or management.”1754

A National Defense University Policy Paper on agricultural bioterrorism specifically cited mutilations in addition to crowding as factors that increase stress levels to a point at which the resultant immunosuppression may play a part in making U.S. animal agriculture vulnerable to terrorist attack.1755 Ian Duncan just stepped down as University of Guelph Animal and Poultry Science Department University Chair. He has been outspoken about the animal and human health implications of these stressful practices. “All these ‘elective surgeries’ involve pain,” Duncan writes, “perhaps chronic pain. No anesthetic is ever given to the birds. These mutilations are crude solutions to the problems created by modern methods of raising chickens and turkeys.”1756

The former head of the Department of Poultry Science at North Carolina State University describes how turkeys start out their lives. Newborn turkey chicks are: squeezed, thrown down a slide onto a treadmill, someone picks them up and pulls the snood off their heads, clips three toes off each foot, debeaks them, puts them on another conveyer belt that delivers them to another carousel where they get a power injection, usually of an antibiotic, that whacks them in the back of their necks. Essentially, they have been through major surgery. They have been traumatized.1757 Research performed at the University of Arkansas’ Center of Excellence for Poultry Science suggests that the cumulative effect of multiple stressors throughout turkey production results in conditions like “turkey osteomyelitis complex,” where decreased resistance to infection leads to a bacterial invasion into the bone, causing the formation of abscessed pockets of pus throughout the birds’ skeletons. USDA researchers blame “stress-induced immunosuppression” in turkeys on their “respon[se] to the stressors of modern poultry production in a detrimental manner.”1758 The stress of catching and transport alone has been shown to induce the disease.1759

If modern production methods make animals so vulnerable to illness, why do they continue? The industry could reduce overcrowding, thereby lowering mortality losses from disease, but, as poultry scientists explain, “improving management may not be justified by the production losses.”1760 In other words, even if many birds die due to disease, the current system may still be more profitable in the short run. “Poultry are the most cost-driven of all the animal production systems,” reads one veterinary textbook, “and the least expensive methods of disease control are used.”1761 It may be cheaper to just add antibiotics to the feed than it is to make substantive changes, but relying on the antibiotic crutch helps foster antibiotic-resistant superbugs and does nothing to stop bird flu.

The leading poultry production manual explains the economic rationale for overcrowding: “[L]imiting the floor space gives poorer results on a bird basis, yet the question has always been and continues to be: What is the least amount of floor space necessary per bird to produce the greatest return on investment.”1762 What remains missing from these calculations is the cost in human lives, which for poultry diseases like bird flu, could potentially run into the millions.