Animal Bugs Forced to Join the Resistance

Click here for a printer-friendly version of this pageAt the American Chemical Society annual meeting in Philadelphia in 1950, the business of raising animals for slaughter changed overnight. Scientists announced the discovery that antibiotics make chickens grow faster.1186 By 1951, the FDA approved the addition of penicillin and tetracycline to chicken feed as growth promotants, encouraging pharmaceutical companies to mass-produce antibiotics for animal agriculture. Antibiotics became cheap growth enhancers for the meat industry.1187

Healthy animals raised in hygienic conditions do not respond in the same way. If healthy animals housed in a clean environment are fed antibiotics, their growth rates don’t change. Factory farms are considered such breeding grounds for disease that much of the animals’ metabolic energy is spent just staying alive under such filthy, crowded, stressful conditions;1188 normal physiological processes like growth are put on the back burner.1189 Reduced growth rates in such hostile conditions cut into profits, but so would reducing the overcrowding. Antibiotics, then, became another crutch the industry can use to cut corners and cheat nature.1190 Mother Nature, however, does not stay cheated for long.

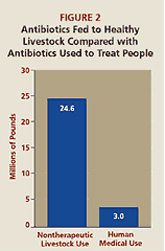

The poultry industry, with its extreme size and intensification, continues to swallow the largest share of antibiotics. By the 1970s, 100% of all commercial poultry in the United States were being fed antibiotics. By the late 1990s, poultry producers were using more than ten million pounds of antibiotics a year.1191 So many antibiotics are fed to poultry that there have been reports of chickens dying from antibiotic overdoses.1192 These thousands of tons of antibiotics are not going to treat sick animals; more than 90% of the antibiotics are used just to promote weight gain.1193 The majority of the antibiotics produced in the world go not to human medicine but to prophylactic usage on the farm.1194 This may generate antibiotic resistance.

When one saturates an entire broiler chicken shed with antibiotics, this kills off all but the most resistant bugs, which can then spread and multiply. When Chinese chicken farmers put amantadine into their flocks’ water supply, there was a tremendous environmental pressure on the virus to mutate resistance to the antiviral. Say there’s a one in a billion chance of an influenza virus developing resistance to amantadine. Odds are, any virus we would come in contact with would be sensitive to the drug. But each infected bird poops out more than a billion viruses every day.1195 The rest of their viral colleagues may be killed by the amantadine, but that one resistant strain of virus will be selected to spread and burst forth from the chicken farm, leading to widespread viral resistance and emptying our arsenal against bird flu. The same principles apply to the feeding of other antimicrobials.1196

According to the CDC, at least 17 classes of antimicrobials are approved for food animal growth promotion in the United States,1197 including many families of antibiotics, such as penicillin, tetracycline, and erythromycin, that are critical for treating human disease.1198 As the bugs become more resistant to the antibiotics fed to healthy chickens, they may get more resistant to the antibiotics needed to treat sick people. According to the World Health Organization, the livestock industry is helping to breed antibiotic-resistant pathogens.1199 “The reason we’re seeing an increase in antibiotic resistance in foodborne diseases,” explains the head of the CDC’s food poisoning surveillance program, “is because of antibiotic use on the farm.”1200 The industry continues to deny culpability.1201

The European science magazine New Scientist editorialized that the use of antibiotics to make animals grow faster “should be abolished altogether.” That was in 1968.1202 Pleas for caution in the overuse of antibiotics can be traced back farther to Sir Alexander Fleming himself, the inventor of penicillin, who told the New York Times in 1945 that inappropriate use of antibiotics could lead to the selection of “mutant forms” resistant to the drugs.1203 While Europe banned the use of many medically important antibiotics as farm animal growth promoters years ago,1204 no such comprehensive step has yet taken place in the United States. Two of the most powerful lobbies in Washington, the pharmaceutical industry and the meat industries, have fought bitterly against efforts by the World Health Organization,1205 the American Medical Association,1206 and the American Public Health Association1207 to enact a similar ban in the United States.1208

Donald Kennedy, the editor-in-chief of Science, wrote that the continued feeding of medically important antibiotics to farm animals to promote growth goes against a “strong scientific consensus that it is a bad idea.”3189 An editorial the same year in the New England Journal of Medicine entitled, “Antimicrobial Use in Animal Feed–Time to Stop,” came to a similar conclusion.3190

Despite the consensus among the world’s scientific authorities, debate on this issue continues. The editorial board of the Nature microbiology journal offered an explanation: “A major barrier is the fact that many scientists involved in agriculture and food animal producers refuse to accept that the use of antibiotics in livestock has a negative effect on human health. It is understandable that the food-producing industry wishes to protect its interests. However, microbiologists are aware of, and understand, the weight of evidence linking the subtherapeutic use of antibiotics with the emergence of resistant bacteria. Microbiologists also understand the threat that antibiotic resistance poses to public health. As a profession, we must be vocal in supporting any policy that diminishes this threat.”3191

An editorial in the Western Journal of Medicine identified erroneous claims made by the pharmaceutical and meat industries and concluded: “The intentional obfuscation of the issue by those with profit in mind is an uncomfortable reminder of the long and ongoing battle to regulate the tobacco industry, with similar dismaying exercises in political and public relations lobbying and even scandal”3192

The U.S. Government Accountability Office released a 2004 report on the use of antibiotics in farm animals. Though they acknowledge that “[m]any studies have found that the use of antibiotics in animals poses significant risks for human health,” the GAO notably did not recommend banning the practice,1209 as a ban on the use of antibiotics as growth promoters could in part result in a “reduction of profits” for the industry. Even a partial ban would “increase costs to producers, decrease production, and increase retail prices to consumers.”

An unsubstantiated industry estimate3194 of the costs associated with a total ban on the widespread feeding of antibiotics to farm animals in the United States would be an increase in the price of poultry anywhere from 1 to 2 cents per pound and the price of pork or beef around 3 to 6 cents a pound, costing the average meat-eating American consumer up to $9.72 a year.1210

Antibiotic-resistant infections in the United States cost an estimated $30 billion every year1211 and kill 90,000 people.1212

A major analysis of the elimination of growth-promoting antibiotics in Denmark, one of the world’s largest pork producers, showed that the move led to a marked reduction in bacterial antibiotic-resistance without significant adverse effects on productivity.3195 U.S. industry, however, has argued that the Danish experience cannot be extrapolated to the United States. This led Johns Hopkins University researchers to carry out an economic analysis based on data from Perdue, one of the largest poultry producers in the United States.

The Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health study, published in 2007, examined data from seven million chickens and concluded that the use of antibiotics in chicken feed increases costs of poultry production. “Contrary to the long-held belief that a ban against GPAs [growth-promoting antibiotics] would raise costs to producers and consumers,” the researchers concluded, “these results using a large-scale industry study demonstrate the opposite.” They found that the conditions in Perdue’s facilities were such that antibiotics did accelerate the birds’ growth rates, but the money saved was insufficient to offset by the cost of the antibiotics themselves. Growth-promoting antibiotics may end up costing producers more in the end than if they hadn’t used antibiotics at all. A similar study at Kansas State University also showed no economic benefits from feeding antibiotics to fattening pigs.3196

The drug companies, though, stand to lose a fortune. When the FDA first considered revoking the license for the use of antibiotics strictly as livestock growth promoters, the drug industry went hog wild. Thomas H. Jukes, a drug industry official formerly involved with one of the first commercial producers of antibiotics for livestock, blamed the FDA’s consideration on a “cult of food quackery whose high priests have moved into the intellectual vacuum caused by the rejection of established values.” Jukes was so enamored with the growth benefits he saw on industrial farms that he advocated antibiotics be added to the human food supply. “I hoped that what chlortetracycline did for farm animals it might do for children.” We should especially feed antibiotics to children in the Third World, he argued, to compensate for their unhygienic overcrowding, which he paralleled to the conditions “under which chickens and pigs are reared intensively.”1213 “Children grow far more slowly than farm animals,” he wrote. “Nevertheless, there is still a good opportunity to use low-level feeding with antibiotics…among children in an impoverished condition.”1214

The poultry industry blames the dramatic rise in antibiotic-resistant bacteria on the overprescription of antibiotics by doctors.1215 While doctors undoubtedly play a role, according to the CDC, more and more evidence is accumulating that livestock overuse is particularly worrisome.1216 Take, for example, the recent September 2005 FDA victory against the Bayer Corporation.1217

Typically, Campylobacter causes only a self-limited diarrheal illness (“stomach flu”) which doesn’t require antibiotics. If the gastroenteritis is particularly severe, though, or if doctors suspect that the bug may be working its way from the gut into the bloodstream, the initial drug of choice is typically a quinolone antibiotic like Cipro. Quinolone antibiotics have been used in human medicine since the 1980s, but widespread antibiotic-resistant Campylobacter didn’t arise until after quinolones were licensed for use in chickens in the early 1990s. In countries like Australia, which reserved quinolones for human use only, resistant bacteria are practically unknown.1218

The FDA concluded that the use of Cipro-like antibiotics in chickens compromised the treatment of nearly 10,000 Americans a year, meaning that thousands infected with Campylobacter who sought medical treatment were initially treated with an antibiotic to which the bacteria was resistant, forcing the doctors to switch to more powerful drugs.1219 Studies involving thousands of patients with Campylobacter infections showed that this kind of delay in effective treatment led to up to ten times more complications—infections of the brain, the heart, and, the most frequent serious complication they noted, death.1220

When the FDA announced that it was intending to join other countries and ban quinolone antibiotic use on U.S. poultry farms, the drug manufacturer Bayer initiated legal action that successfully hamstrung the process for five years.1222 During that time, Bayer continued to corner the estimated $15 million a year market,1221 playing its game of chicken with America’s health while resistance continued to climb.3188

Meanwhile, poultry factories continue to spike the water and feed supply with other antibiotics critical to human medicine. Evidence released in 2005 found that retail chicken samples from factories that used antibiotics are more than 450 times more likely to carry antibiotic-resistant bugs. Even companies like Tyson and Perdue, which supposedly stopped using antibiotics years ago, are still churning out antibiotic-resistant bacteria-infected chicken. Scientists think bacteria that became resistant years before are still hiding within the often dirt floors of the massive broiler sheds or within the water supply pipes. Another possibility is that the carcasses of the chickens raised under so-called “Antibiotic Free” conditions are contaminated with resistant bacteria from slaughterhouse equipment that can process more than 200,000 birds in a single hour.1223

Relying on the poultry industry to police itself may not be prudent. This is the same industry that pioneered the use of the synthetic growth hormone diethylstilbestrol (DES) to fatten birds and wallets despite the fact that it was a known carcinogen. Although some women were prescribed DES during pregnancy—a drug advertised by manufacturers to produce “bigger and stronger babies”1124 —the chief exposure for the American people to DES was through residues in meat. Even after it was proven that women who were exposed to DES gave birth to daughters plagued with high rates of vaginal cancer, the meat industry was able to stonewall a ban on DES in chicken feed for years.1225 According to a Stanford University health policy analyst, only after a study found DES residues in marketed poultry meat at 342,000 times the levels found to be carcinogenic did the FDA finally ban it as a growth promotant in poultry in 1979.1226

Science editor-in-chief Dr. Kennedy, who served as commissioner of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, describes the antibiotic debate as a “struggle between good science and strong politics.” When meat production interests pressured Congress to shelve an FDA proposal to limit the practice, Kennedy concluded: “Science lost.”2193

The industry defends its antibiotic-feeding practices. Before Bayer’s antibiotic was banned, a National Chicken Council spokesperson told a reporter, “It improves the gut health of the bird and its conversion of feed, what we call the feed efficiency ratio…. And if we are what we eat, we’re healthier if they’re healthier.”1227 Chickens in modern commercial production are profoundly unhealthy. Due to growth-promoting drugs and selective breeding for rapid growth, many birds are crippled by painful leg and joint deformities.1228 The industry journal Feedstuffs reports that “broilers now grow so rapidly that the heart and lungs are not developed well enough to support the remainder of the body, resulting in congestive heart failure and tremendous death losses.”1229

The reality is that these birds exist under such grossly unsanitary conditions, cramped together in their own waste, that the industry feels forced to lace their water supply with antibiotics. “Present production is concentrated in high-volume, crowded, stressful environments, made possible in part by the routine use of antibacterials in feed,” the congressional Office of Technology Assessment wrote as far back as 1979. “Thus the current dependency on low-level use of antibacterials to increase or maintain production, while of immediate benefit, also could be the Achilles’ heel of present production methods.”1230

In June 2005, the CDC released data showing that antibiotic-resistant Salmonella has led to serious complications.1231 Foodborne Salmonella emerged in the Northeast in the late 1970s and has spread throughout North America. One theory holds that multidrug-resistant Salmonella was disseminated worldwide in the 1980s via contaminated feed made out of farmed fish fed routine antibiotics,1232 a practice condemned by the CDC.1233 Eggs are currently the primary vehicle for the spread of Salmonella bacteria to humans, causing an estimated 80% of outbreaks. The CDC is especially concerned about the recent rapid emergence of a strain resistant to nine separate antibiotics, including the primary treatment used in children.1234 Salmonella kills hundreds of Americans every year, hospitalizes thousands,1234 and sickens more than a million.1236

The Director-General of the World Health Organization fears that this global rise in antibiotic-resistant “superbugs” is threatening to “send the world back to a pre-antibiotic age.”1237 As resistant bacteria sweep aside second- and third-line drugs, the CDC’s antibiotic-resistance expert says that “we’re skating just along the edge.”1238 The bacteria seem to be evolving resistance faster than our ability to create new antibiotics. “It takes us 17 years to develop an antibiotic,” explains a CDC medical historian. “But a bacterium can develop resistance virtually in minutes. It’s as if we’re putting our best players on the field, but the bench is getting empty, while their side has an endless supply of new players.”1239 Remarked one microbiologist, “Never underestimate an adversary that has a 3.5 billion-year head start.”1240

For critics of the poultry industry, the solution is simple. “It doesn’t take rocket science,” said the director of the Union of Concerned Scientists’ food division, “to create the healthy, non-stressful conditions that make it possible to avoid the use of antibiotics.”1241 The trade-off is between immediate economic benefit for the corporations and longer-term risks shared by us all, a theme that extends to the control of avian influenza.1242

In 2004, the Worldwatch Institute published an article, “Meat: Now, it’s not personal!”1243 They were alluding to intensive methods of production that have placed all of us at risk, regardless of what we eat. In the age of antibiotic resistance, a simple scrape can turn into a mortal wound and a simple surgical procedure can be anything but simple. But at least these “superbugs” are not effectively spread from person to person. Given the propensity of factory farms to churn out novel lethal pathogens, though, what if they produced a virus capable of a global pandemic?